Jamna Lal shifts around uncomfortably on his rugged old Charpoy bed, seemingly unable to digest the fact that he may have been responsible for the death of his two-year-old daughter last year.

He ponders the possibility for some time and then eventually, nods his head. ‘Yes, I’m also responsible, I decided to take her to the Bhopa instead of the hospital, and I must suffer the consequences.’

Jamna’s two-year-old daughter Kushbu had been suffering with breathing problems in January, last year, but, like many families in villages around Bhilwara, in Rajasthan, southern India, Jamna did not immediately think of the hospital to treat his sick toddler.

The communities across this area of the state believe in Bhopas, or witch doctors as they’re more commonly known, who believe in the traditional use of a hot piece of iron, clay or cloth, burned onto the chest of a toddler believing it will burn a particular nerve to cure the child of certain illnesses. More often than not, the child’s condition gets worse, and is rushed to hospital.

Little Kushbu had a hot piece of clay burned into her chest but after her condition worsened and was rushed to hospital where she battled to survive for eight days, she sadly died.

‘My ancestors have been doing this for many years,’ Jamna, 65, says. ‘We all do it. We took my older daughter Naraya to the Bhopa when she was little too and she got better and we thought Kushbu would get better too.’

Jamna was giving Kushbu a traditional Hindu cremation the next day, when the police arrested him and retrieved the little girl’s body for a postmortem.

‘I had no idea why the police were there,’ says Jamna, who works as a farmer and a daily labourer, often earning just 300 rupees (£3.30) a day.

But, Jamna had in fact committed a crime. In India, under the Juvenile Justice Act 2015, he had recklessly ignored her safety by taking her to the ‘Bhopa’.

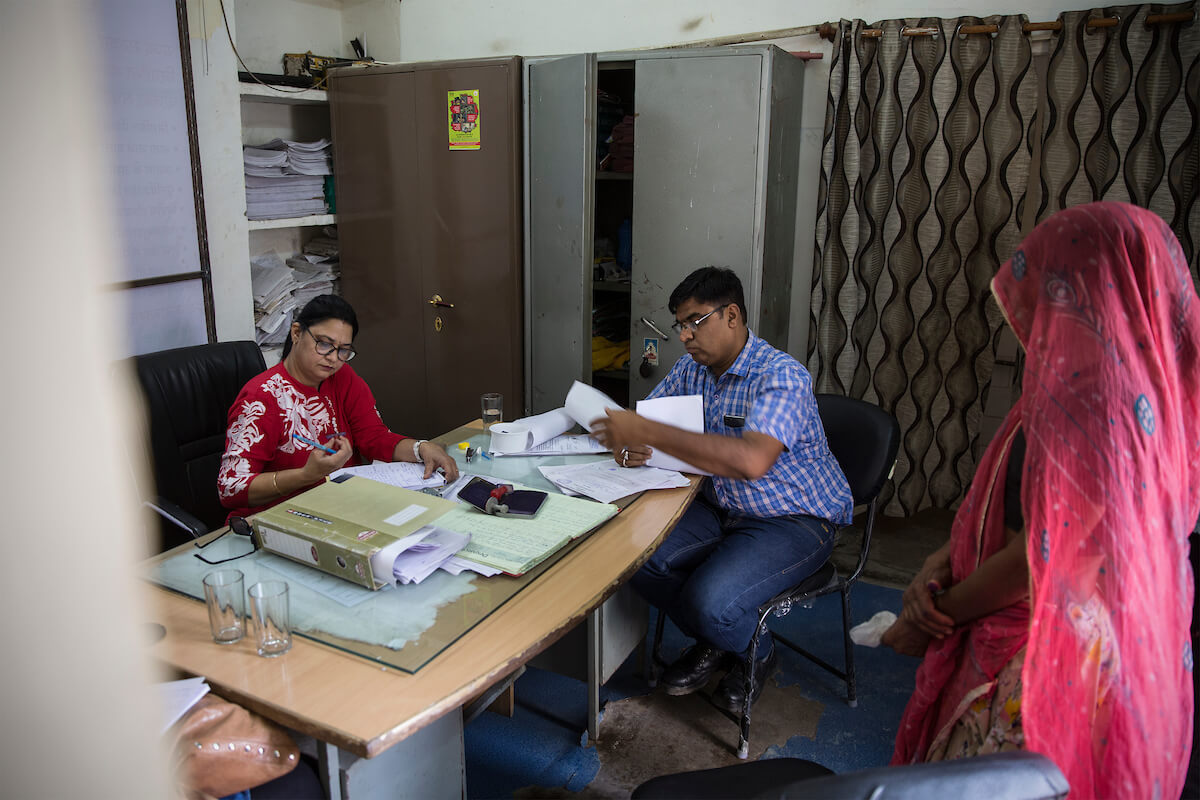

Ever since Rajasthan’s Child Welfare Committee chairperson, Suman Trivedi, 47, was appointed she has been rigorously working on ending the child branding tradition plaguing her area. And the law is thankfully on her side.

‘When I was a social worker I was faced with many frustrating injustices but I had little power to do anything,’ the mother of two says. ‘But through the Child Welfare Committee I have powers to make real change.

‘Earlier, every time I read a newspaper article about another innocent child being branded I was desperate to do something,’ Suman says. ‘When I found out no NGO or organisations were looking into it I decided to commit some real time to the issue. I found the Juvenile Justice Act covers child cruelty and I decided to use the law to implement change.’

Suman instructed hospitals across Bhilwara to inform her when a branding case was admitted. And since 2016, due to her unwavering commitment, even though three children have died, she has 14 strong cases lodged with the police, waiting to go to trial.

One of those criminals is the witch doctor responsible for branding Kushbu, 70-year-old Ladi Vaieshnav. And ever since the police arrested her and she spent 17 days in prison, she has been terrified of speaking about her 20-year career as a ‘Bhopa’.

She eventually explains: ‘I’ve treated around 40 children over the last 20 years but not one has ever died. I was shocked and felt pain when I heard of the death of the little girl but the father wanted me to do it. He came to me.

‘I learned the methods from another (Bhopa); many years ago. I don’t know how but these babies would be cured within 20 minutes of the branding. It worked many times.’

Her 35-year-old son, Satyanarayan, who has a branding scar on his chest, says: ‘She’s spent years doing good. Many babies have been cured. But something went wrong this time.’

Ladi, who is awaiting trial, insists she’s never branding another baby again. ‘I tell everyone I’m no longer doing it,’ she adds. ‘And I tell other Bhopas to stop. Things can go wrong, and these children should go to the hospital.’

Suman understands how the issue has spiraled out of control. ‘It’s due to a lack of education, and the levels of illiteracy in these parts,’ she explains. ‘The government’s health care is not reaching the grass roots, and these communities think the old remedies will heal their child.’

But she believes she is getting results. ‘The first time we lodged a case with the police there was a lot of opposition. The parents got angry. But branding a child is wrong. If you make a chapatti, and dip it in hot oil it’ll burn your skin. These parents are burning materials and branding their babies. How must the child feel? They can’t express their pain but cry.

‘I know the parent’s intentions are not bad, they want their child to get better, but they don’t realise the path they’re choosing is the wrong one. I need to make people aware that it’s a crime and I have to make some strict decisions. But the results speak for themselves. There are less branding issues today because people are aware that if they’re caught I will lodge a case against them and they’re scared now.’

However, while Bhopas are claiming to have stopped the practise, many elder members of the family are still using the techniques.

Grandmother Panibai, 65, from a village outside Bhilwara, saw her three-year-old grandson Sundar suffering with fever and dehydration, last summer, before she took the decision to burn a corner of her sari in the fire pit and brand his chest three times. But within 24 hours he got worse and spent the next six days in hospital.

Her son Raju Kalbaliya, 35, has a branding scar on his chest too. He understands why his mother branded his son but admits he felt bad when he heard. ‘My mother did what she had to do,’ he says. ‘There’s no medical assistance in these parts so we have this custom and it’s worked for many babies here.

‘But I felt pain when I heard my son had experienced this. I know it’s not good, and I’m telling the community it’s not good. We should use the hospitals for the sake of our children.’

Panibai was arrested and is awaiting trial. If found guilty she faces a hefty fine and a minimum three years in prison for child cruelty.

Dr Radhe Shayam Shrotriya, head of pediatrics, at the government Medical College Bhilwara hospital, says he’s seen 11 cases of branding at the hospital over the last two years.

‘These children are brought here very sick and it becomes very difficult to treat them. The branding is on the abdominal wall, sometimes an incision, sometimes a thumb print type, but the parents do not understand what they’re doing is wrong.

‘When we find out they’ve been branded we call the police, and since doing this over the last two years we’ve seen the numbers drop. But we can’t just punish the parents, we need to counsel them. If their babies are ill, they should go to the hospital. These parents don’t want to kill their baby, but these parents are ignorant and very misguided, I feel much empathy for them.’

Naresh Pareek, 42, from the Mewar Sewa Sansthan charity, backed by Plan International, is a member of the Child Welfare Committee and has worked alongside Suman for the last two years. ‘We’ve faced a lot of challenges as we’ve pressured these communities to stop. But people are aware now, and they know of the consequences. People get angry with us but we face their anger. I feel it’s our moral obligation.’

Suman adds: ‘I think we’re on the right path. There has already been a decline in branding cases and even if it will take a number of years, it will disappear from our society in the end.’

Jamna Lal looks at a small passport size photo of his daughter and admits he has regret, but it’s regret that he didn’t take his daughter to the hospital in time. ‘I lost my child, I will never get her back. I will not use Bhopas again, we must use hospitals.’